Naked Truths: Lucian Freud at the Pompidou

Mon 3 May 2010

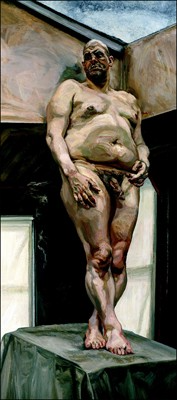

Lucian Freud, Leigh under the Skylight, 1994. Oil on canvas. © Lucian Freud Photo © DR

In Paris the artist’s studio holds eternal fascination. Onetime workplaces turned into museums fill the city, and every week lifestyle magazines offer us peeks into new ateliers. Thus it’s no surprise that the Pompidou’s current show by Lucian Freud—at 88, considered by many the world’s greatest living artist—has been organized around its subject’s studio.

Many blockbuster exhibitions have celebrated this artist’s classic yet controversial portraits. But by focusing on the intimate world in which Freud makes them, “Lucian Freud: L’Atelier,” curated by Cécile Debray, helps us understand how he sees. Her decision also refreshes the fundamental story of how an artist captures what it means to be human. The show, which is on view through July 19, 2010, assumes this English eccentric belongs to Europe—and that he is equal to names such as Matisse, Velázquez, Ingres or Titian. All are masters at facing a sitter in the studio.

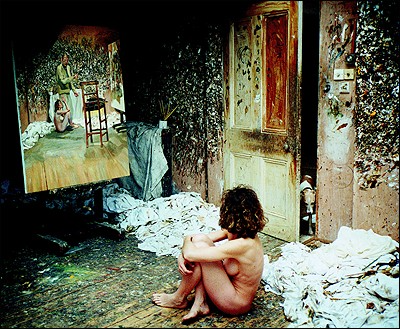

David Dawson, Naked Admirer, 2004. Photograph. © David Dawson, courtesy Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, Londres

Staged with great panache, the show is irresistible and has had Parisians queuing right along with the tripists. Some of their interest, however, is in Freud’s notoriety. The grandson of Sigmund Freud, this artist has created some of the most extreme, defiant nudes in the history of art. He is also a well-known Lothario who has fathered a number of illegitimate children.

Many of these progeny are prominent in English society, but their father always enjoyed his own social connections. These have allowed him to paint Britain’s Queen Elizabeth (not, however, in the nude), as well as celebrity artists from Christian Bérard to Francis Bacon—and models including Kate Moss and Jerry Hall. The exhibition’s final room is filled with giant portraits, many of fringe personalities such as Divine and Leigh Bowery.

David Dawson, Working at Night, 2005. Photograph. © David Dawson, courtesy Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, Londres

Here one also finds Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, a painting that sent shock waves through the art world. It depicts plus-size Londoner Sue Tilley at rest on a couch, her ample flesh almost like an overwhelming force of nature. Tilley—a fixture of London’s nightclub scene in the early 1990s—is well known in Paris. (For a 2006 project at the Grand Palais, photographer Jacques Bosser created stunning, Kabuki-like portraits of her.) Benefits Supervisor Sleeping is also famous for setting a record for a work by a living artist; it fetched $33.6 million at auction in New York in 2008.

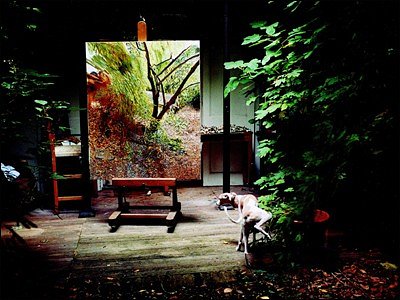

David Dawson, Painter’s Garden with Eli, 2006. Photograph. © David Dawson, courtesy Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert, Londres

His fame and the hefty value of his works aside, Freud’s life has always been centered in his studio. The first work in the show, The Painter’s Room, may explain why. This 1944 piece depicts a theatrical workspace, occupied only by a couch, a plant, a drape and an old top hat. A zebra pokes its head unexpectedly through the window. The absent artist seems to be saying, “In this place, anything is possible.”

The paintings that follow challenge us to see people just as Freud does: carnal, complicated and anything but pretty. Yet the Pompidou’s wonderful lighting reveals the energy of his furious strokes and elaborate textures. At first glance, many of the bodies seem slightly grotesque—until Freud fills our eyes with just how alive they are. His portrait of Tilley sleeping already moved one critic to call it the equal of Manet’s Olympia. Since this Manet hangs in the Musée d’Orsay, why not visit both and see if you agree?

Lucian Freud, Reflection with Two Children (Self-Portrait), 1965. Oil on canvas. Photo © José Loren, Museo Thyssen-Bornemiska, Madrid © Lucian Freud

Tip Sheet: Famous Parisian Ateliers to Visit

Le Bateau-Lavoir

As studio-home to Picasso and others, this former piano factory (its name means “the laundry barge”) saw the birth of Cubism—Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was painted here. The facade, on Place Emile-Goudeau, remains as it was; the rest of the building had to be reconstructed after a fire. It is a national landmark.

Musée Bourdelle

A museum, with wonderful gardens, created around the 1885 atelier of sculptor Emile-Antoine Bourdelle, who grew from Rodin’s apprentice into Giacometti’s teacher.

Musée National Eugène Delacroix

The studios, with garden, where the painter lived and worked from 1857 to 1863.

La Ruche

Nicknamed “the beehive,” this unique building was originally Gustave Eiffel’s wine pavilion for the 1900 Exposition. Rebuilt by Albert Boucher, La Ruche housed artists such as Chagall, Modigliani and Diego Rivera. With help from the likes of Sartre and Alexander Calder, it was restored for artists’ use in the 1970s.