Louis Vuitton’s Luxury Odyssey: Time Travel à la Mode

Mon 3 Jan 2011

Fantasy of photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue on the theme of Louis Vuitton, 1978. Fondation Jacques-Henry Lartigue.

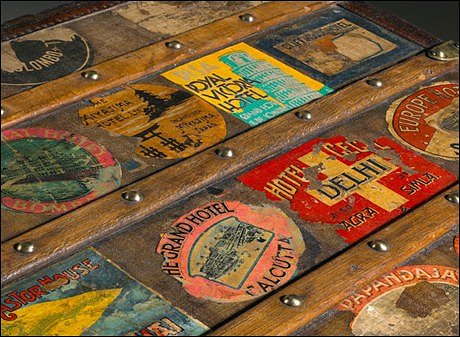

No matter how seductive those airline or cruise ship ads, travel today is often more trying than glamorous. Hence the special appeal of Travel Capital: Louis Vuitton & Paris, on view at the Musée Carnavalet through February 27, 2011. This multimedia exhibition takes visitors back to moments which, since the mid-19th century, made Paris that city we know. You might think it’s all just stacks of beautiful baggage. Au contraire! Stuffed with fashion, history and savoir faire, the show leaves not one drawer of its famous trunks unopened.Louis Vuitton himself arrived in Paris in 1837, to begin training as a malletier, or luggage maker. As an employee of the firm of Maréchal, he noticed two things. One was how complicated women’s dress was becoming. The other was how many people were traveling, making use of new omnibuses, steamers and trains. Vuitton saw a wide-open business opportunity, one he aimed to fill by inventing special luggage. So he created cases for items such as huge crinolines, cases that could be stacked together, light in weight and waterproof.

Men’s Vuitton travel trunk, 1885. Photo: Collection Louis Vuitton

His ideas proved perfectly in step with the times. By the 1850s everything in Paris was changing. Napoleon III declared himself emperor, founded a court of nouveaux riches and put Baron Haussmann to work. The baron’s rebuilding orgy changed more than architecture. Its grand boulevards altered Parisian life forever. Between 1830 and 1860, the population doubled and places to see and be seen sprang up everywhere: new cafés, parks, theatres and the Opéra.

This transformation kept retailers busy—and Vuitton’s creativity fascinated consumers. Yet French shoppers still believed the finest luggage was British. Their love of London’s leathers dated back to the 1770s, to a Parisian vogue for “English country style.” It was not Louis Vuitton but his son Georges who finally figured out how to surmount this prejudice.

Portrait of Louis Vuitton (1821–92). Photo: Collection Louis Vuitton

Louis Vuitton founded his own house in 1854. He gained the clout to do it from Empress Eugenie, who had put him in charge of designing the royal luggage. Louis entered the big time with flamboyance, opening his store in the modish 9th Arrondissement. Across the street from his maison, Garnier was erecting the Opéra; almost next door, Worth was dressing the Court. Visitors poured through nearby Gare St.-Lazare, many of them staying on Vuitton’s street at the Hôtel Scribe.

In a special studio outside Paris, Vuitton’s team scrambled to create trunks for all their travel needs. These trunks could hold anything from top hats to crystal bottles. In 1855, when Georges joined the company, he brought skills that solidified the business. Georges oversaw the opening of a London maison, to dispense Louis’s innovations among his chief rivals. When the house was hit by a wave of forgeries, Georges changed the canvas that covered every piece. Vuitton’s famous monogram toile was his design—a pattern deliberately made complex to foil imitators. Within five years, Vuitton’s goods were the talk of Europe.

Polish piano great Paderewski’s toilette case, in sealskin, 1931. © Patrick Gries

The exhibition introduces everyone in the family. But its heart remains with the dazzling goods they created, often collaborations with celebrities, royals or dandies. Here the pieces are presented as part of a changing Paris. Watching the city as Vuitton evolves means marveling over rare scale models of vanished landmarks, staring at replicas from every Great Exhibition and blinking at a “virtual trip” filmed in 1900.

You’ll see the shifts in Parisian life as the train invades, followed by the automobile and, finally, the airplane. War breaks out and Vuitton makes fabulous field gear. The era of art deco helps the house revolutionize hand luggage. When Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza needs a bed to colonize Africa, Vuitton makes him one that folds out of a trunk. Anything a customer can imagine, Louis Vuitton makes—always with impeccable elegance and craftsmanship.

Coffret with vise in monogram fabric, 1910. © Patrick Gries

Every change in travel or taste brings special requests. Thus, here are composer Igor Stravinsky’s portable desk, Mary Pickford’s Hollywood wardrobe trunk, Manolo Blahnik’s shoe case. There are countless items by and for great names past and present.

Jean-Marc Gady, the exhibition scenographer, says Vuitton’s rarities could be matched only by those of the city. So he borrowed hundreds of items (photos, fabrics, films and ephemera) from every major museum in Paris. “I wanted it to be a graphic trajectory,” he says. “One where you could ride inside an early Vuitton trunk, feel the breeze on a 1920s cruise ship and climb the Eiffel Tower—with the excitement of its very first visitor.”

One has to say he has succeeded quite wickedly. Over-the-top luxury has never looked so seductive.

“Travel Capital: Louis Vuitton & Paris,” at the Musée Carnavalet, is open Tuesdays to Sundays through February 27, 2011, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. (Closed Mondays and holidays.) Enjoy a virtual trip of the show’s highlights. For the perfect souvenir (or if you can’t attend) there is always the gorgeous tome Louis Vuitton: 100 Legendary Trunks.

Want more Vuitton? At the flagship store on the Champs Elysées, the Espace Culturel Louis Vuitton features art exhibitions that change three times a year. Through January 9, 2011, they are showing “Who are you, Peter?” The exhibition includes 13 young artists who describe their visions of Peter Pan.

Editor’s note: Try the Girls’ Guide concierge service if you want to have everything taken care of for you while you are in Paris, for surprisingly reasonable rates.