Femmes Fatales at the Musée d’Orsay: Sex, Sin and the Guillotine

Sun 4 Apr 2010

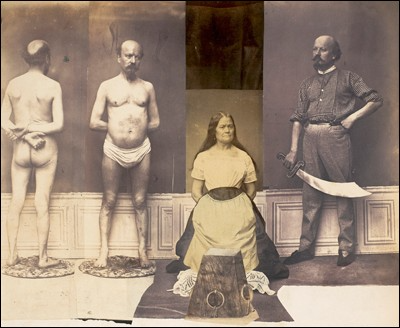

Anonymous, Obsession No. 1, ca. 1870. Photocollage, Musée d’Orsay. © RMN (Musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski.

“When artists turn their talent to crime . . . ” is one slogan advertising the Musée d’Orsay’s blockbuster show “Crime et Châtiment” (Crime and Punishment), on view through June 27. It’s a large exhibition (450 pieces) and a provocative one, but also fascinating. With a range of painters, from those we think of as academic—like Théodore Géricault and Edgar Degas—to Expressionists such as Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele, it reveals a fixation on crime equaling that of modern TV news. In addition to famous artists, you’ll meet famous criminals. Films have featured some of them, such as Violette Nozière (Isabelle Huppert plays the teenage poisoner) and Les Enfants du Paradis, which portrays poet-murderer Pierre-François Lacenaire—the inspiration behind Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment.

At the show’s center sits the ultimate femme fatale, an actual guillotine from 1872. Fourteen feet tall, slim and draped in a steel-gray veil, the Revolution’s notorious louisette appears strangely feminine. She is accompanied by a quote from Victor Hugo (“One can have a certain indifference to the death penalty as long as one has not seen a guillotine with one’s own eyes”). One of Andy Warhol’s famed “Electric Chair” prints also hangs nearby, a reminder that the fight against capital punishment has not been won everywhere.

France abolished the death penalty in 1981, after a fight led by then–justice minister Robert Badinter. As a lawyer, M. Badinter witnessed his own client guillotined, a trauma that turned him into a fierce foe of capital punishment. As an adviser to the exhibition, he insisted on the guillotine: “It was impossible not to have her here. Because, at last, she is reduced to an object of curiosity, she is just another antique in a museum.”

Criminals started to feature in French art during the Revolution, when the revolutionary assembly opened trials to the public. Suddenly an artist could attend any hearing and watch the accused as the crime was being described. This experience, along with a growing tabloid press, helped transform many criminals into celebrities.

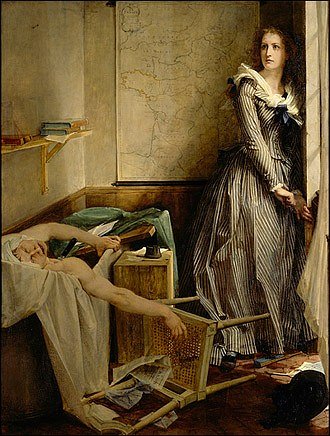

Jean-Joseph Weerts, Marat assassiné! 13 juillet 1793, 8h du soir, 1880. Oil on canvas. Roubaix, La piscine, musée d’art et d’industrie © Photographie Arnaud Loubry.

One of the first was Charlotte Corday, the 24-year-old assassin of Jean-Paul Marat. Her 1793 story has plenty of drama—while the radical revolutionary Marat was one of the most famous men in Paris, Corday was a pretty unknown. She traveled from the country specifically to commit the murder, buying a knife in Paris, then hiding it in her corset. After convincing Marat’s dubious wife to let her see him, Corday plunged her stiletto into his chest. Her sex, youth and daring gave artists a perfect subject—but the exposition shows their different views of her character. Jacques-Louis David’s classic memorial carefully ignores her presence. But, in others, Corday is the central character. Paul Jacques Aimé Baudry shows her as driven yet fragile (above, middle), Jean-Joseph Weerts as overwhelmed by what she has done (above, bottom). To Munch, she is a villainess, the ultimate faithless female.

The show covers many themes, including Romantic petty criminals, Surrealist murder and 19th-century crime scene photos. You may not want to linger over everything. But look out for Victor Hugo’s moving drawings, Cézanne’s famous Murder and Van Gogh’s stunning Prisoner’s Patrol. In each of these, the artist’s own dread adds to a scary scenario—and, voyeuristic or not, each is wonderful art.

“Crime and Punishment” is on view at the Musée d’Orsay through June 27. The museum is offering a large selection of talks, events, movies and concerts connected with the exhibition. One is a five-part crime novel for 15- to 25-year-olds, written for mobile phones by Malika Ferdjoukh. Download it from SmartNovel.